Is there a case for selective, rather than routine, preoperative laryngoscopy in thyroid surgery?

Introduction

Recent data on surgery for thyroid malignancies show an annual incidence of 7-9 per 100,000 inhabitants (1-3). Since malignant thyroid tumors account for 25-30% of all thyroid procedures, the number of procedures carried out for all thyroid diseases may easily be as high as 30-40 per 100,000 habitants. When performed by experienced surgeons, thyroidectomy is a highly safe procedure, with a low risk of injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLN). Although preoperative and postoperative laryngeal function assessment has been proposed as the standard of practice in patients scheduled for thyroid surgery, its routine use is controversial and the data are conflicting (4,5).

Much attention has been directed to postoperative voice changes due to vocal fold palsy (VCP) secondary to injury to the RLN. The prevalence of VCP immediately after surgery varies between published series but may be as high as 9-10% (6). Most of these cases are temporary and patients recover within 12 months after surgery. Permanent postoperative VCP occurs in 2-3% of patients undergoing thyroid surgery. However, prevalence figures greatly vary depending on the adopted policy regarding postoperative laryngeal exam, as they are roughly twice as high if a laryngeal exam is performed routinely rather than only in those patients with postoperative hoarseness (7). Thus, the rates of postoperative VCP reported in the literature may underestimate the real prevalence.

The use of routine postoperative laryngoscopy has been further endorsed by the progressive implementation of intraoperative neural monitoring (IONM) of the RLN. Postoperative laryngoscopy provides additional information allowing maximum interpretation of the data obtained from IONM, rules out many cases of postoperative voice changes in which vocal cord function is normal, and has implications regarding the safety of future, contralateral surgery. All of these reasons have been cited in recommending the routine use of laryngoscopy after thyroid surgery as the standard of care (8).

The rationale for the use of preoperative routine laryngoscopy as the standard of care in thyroid surgery use is based on four arguments:

- There is a significant risk of detecting a preoperative VCP in patients with normal phonatory function;

- VCP may preoperatively suggest invasive malignancy;

- When found at surgery, a nerve invaded by tumor may be better managed if there is previous knowledge of its functional state;

- The data provide an accurate baseline for postoperative laryngeal assessment.

In addition to identifying VCP due to invasive thyroid malignancy, preoperative laryngoscopy can aid in identifying patients with VCP of idiopathic origin or due to previous neck surgery or other, unusual causes. Preoperative detection of VCP also safeguards the surgeon from potential postoperative litigation when the condition first manifests postoperatively (9). Furthermore, the use of IONM requires knowledge of preoperative vocal cord function as an optimal basis for accurate intraoperative monitoring (8). Finally, an accurate surgical quality assessment through a postoperative vocal cord examination relies on precise knowledge of preoperative vocal cord function.

Direct fiber-optic laryngoscopy can be easily performed with very little training such that all endocrine surgeons should be competent at vocal cord evaluation. In fact, the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons is in the process of developing courses in basic laryngeal fiber-optic evaluation (10). This can be interpreted as a clear change in policy, as in their 2001 and 2010 guidelines there is no mention of a preoperative endoscopic evaluation (11,12).

Nonetheless, there is also substantial support for a more selective preoperative approach, given that patients without risk factors are highly unlikely to harbor a preoperative VCP (13-16). Additionally, most units do not have the appropriate equipment to carry out a preoperative direct laryngoscopy. Moreover, surgeons involved in high-volume practices and thus lacking the time to perform the procedure routinely would need to refer a considerable number of patients to an otorhinolaryngology department, which may delay surgery. An alternative is indirect laryngoscopy by mirror examination, which in most cases is a very simple procedure that provides an indirect view of the vocal cords.

Here we apply an evidence-based approach to analyze the prevalence of preoperative VCP and the risk factors that may predict it. We also review the recommendations provided by different professional bodies.

Etiology of vocal cord paralysis

Functional impairment of the RLN may result from a variety of causes and the damage or injury sustained can occur anywhere along their anatomical course. The etiology of RLN paralysis can be divided into three main causes: surgery-related, tumor invasion, and idiopathic. This was confirmed in a review published by Myssiorek et al., in which surgical injury was the most frequent etiology (30-45% of the cases), followed by direct nonlaryngeal tumor invasion (15-30%), and other causes including idiopathic injury (10-25%) (17).

Carotid endarterectomy, thyroid surgery, an anterior approach to the cervical spine, cardiothoracic surgery, and skull-base surgery are the most common operations causing a RLN injury. Although thyroid surgery remains the single most common operation associated with paralysis, the improved techniques for thyroid surgery and the increasing implementation of the other, above-mentioned non-thyroid procedures have increased the relative incidence of the latter as the major cause (18). The prevalence of postoperative VCP in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy is 2-6%, with functional improvement or complete recovery ranging from 50% to most of these patients.

Events associated with endotracheal intubation are also worth considering. Endotracheal intubation due to different mechanisms accounted for 7% to 11% of RLN paralysis in several larger series, although most patients recovered spontaneously within 6 months (17).

Other, less frequent etiologies of VCP include viral infections, drug induced, jugular vein thrombosis, central venous access procedures, stroke and diabetic neuropathy. Laryngeal dysfunction may also occur with infarcts of the brain, especially of the medulla. This is usually accompanied by dysfunction of the pharyngeal and laryngeal branches of cranial nerves IX and X along with ipsilateral VCP, leading to swallowing difficulty and aspiration. In a series of patients who underwent thyroid surgery, the preoperative prevalence of VCP was 10-fold higher in those with diabetic neuropathy (19). This relationship should be taken into account during the preoperative workup of patients undergoing thyroid surgery.

Finally, there are also a considerable number of cases of VCP without obvious cause. These idiopathic cases account for 10-20% of all VCPs.

Reported prevalence of preoperative vocal cord paralysis

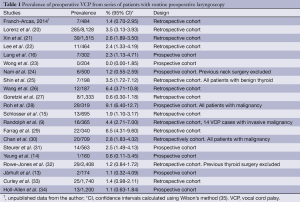

The prevalence of VCP in patients who underwent routine laryngoscopy as part of the preoperative workup for thyroid surgery has been retrospectively reviewed in several case series. The data reported in those studies greatly vary, given that the characteristics of the included patients (e.g., the proportion with a malignant thyroid tumor and the inclusion of patients with revision procedures or previous neck surgery) may modify the determined preoperative risk of VCP.

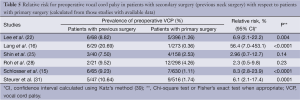

This review considers 20 case series in which patients scheduled for thyroid surgery underwent routine preoperative laryngoscopy (9,13-16,20-34). Most of the included series are retrospective. We also made use of data extracted from the database of endocrine surgery patients treated in our department from 2007 to 2013 (Franch-Arcas et al., unpublished data). Because all of the reviewed data involve series with small numbers of patients, the prevalence should be interpreted with caution. Data from the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Excluding series with <200 patients and others based only on patients with malignancies, the prevalence of preoperative VCP ranges from 1% to 6%.

Full table

Asymptomatic vocal fold palsy

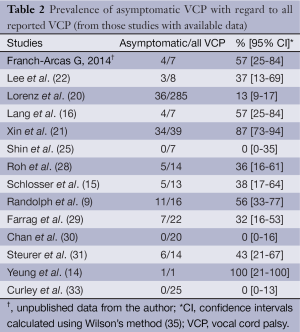

Patients with VCP may be asymptomatic, due to variable remaining vocal cord function as well as variability in the position of the paralyzed vocal cord and functional compensation by the contralateral vocal cord. Slow-growing tumors that infiltrate or surround the nerve generally allow compensation for paralysis such that even in the presence of an immobile cord, symptoms may not be evident. Similarly, in patients with long-standing benign goiter, progressive stretching of the laryngeal nerve may allow for functional compensation. Even in the case of a permanent symptomatic VCP, the symptoms may improve with time and even disappear, falsely suggesting that the paralysis has resolved. In a study of 98 patients with paralyzed cords of different etiologies, as many as 19 patients were asymptomatic (36). Data on the prevalence of asymptomatic VCP among all reported cases of VCP were available for 13 out of the 20 studies included in this review (Table 2). They show that asymptomatic VCP is not rare at all and may account for >50% of all VCPs.

Full table

There is some debate on whether the definition of “voice symptoms” should be considered as those complaints referred by the patient or the subjective evaluation by the surgeon. In the study by Lee et al. the prevalence of preoperative voice symptoms was 39% of patients if any voice complaint referred by the patient was registered as “voice symptoms”, whereas this prevalence dropped to 4% if only surgeon-documented voice abnormalities were considered (22). Recent guidelines from the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation recommends the use of more objective methods for assessing patient’s preoperative voice, including patient self-report scores, audio-perceptual judgment and acoustic measurement of audio recordings (37).

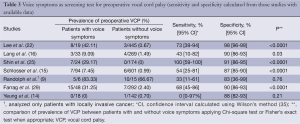

The sensitivity and specificity of the presence of voice symptoms as a screening test for preoperative VCP is shown in Table 3. In most of the studies, sensitivity did not reach 75%. Sensitivity was lowest in the study by Randolph et al.: 33% had symptoms and 66% were asymptomatic (9). Within the total group of 365 patients undergoing thyroidectomy, there were 16 cases of preoperative VCP and all but one were attributable to locally invasive thyroid cancer. Since in that study sensitivity was calculated only from the group of 21 patients with invasive cancer, the confidence interval for the sensitivity determination is very broad (11-61%). Accordingly, the sensitivity of 33% should not be universally extrapolated. As discussed above, a long-standing, slow-growing tumor may allow for contralateral compensation and thus obscure symptoms. The >85% specificity determined for most of the studies means that among patients without VCP >85% will also not have voice symptoms, but 15% will have voice symptoms.

Full table

We can therefore conclude that voice symptoms are not a good predictor of the presence of VCP. While they may contribute to a preoperative diagnosis or suspicion of VCP, their presence is by no means pathognomonic.

Thyroid cancer

Hoarseness and VCP in a patient with a thyroid nodule have long been considered as indicative of advanced thyroid cancer. In the study by Randolph et al. (9), the presence of preoperative VCP had an excellent predictive value for the detection of invasive thyroid cancer at surgery (sensitivity 76%, specificity 100%). However, as commented above, these figures must be interpreted with caution since all but one of the cases of VCP in that study were occurred in patients with invasive cancer.

Local invasion seems to be the main reason for the increased risk of VCP in patients with thyroid cancer. However, locally advanced cancer may not always be diagnosed preoperatively and the suspicion or diagnosis of thyroid cancer may be enough to justify performing a laryngoscopy as part of the preoperative workup. This is especially true for patients with tumors that are not anterior in their anatomical location—that is, at a distance from the course of the RLN—and where the presence of extrathyroidal invasion is difficult to confirm. If preoperative VCP is encountered, radiological and other diagnostic workups may be expanded accordingly and surgical planning will need to consider a more complex procedure. Furthermore, when found at surgery, a nerve invaded by tumor may be better managed if there is previous knowledge of its functional state. A functional nerve should be preserved providing that there is no residual gross disease (38).

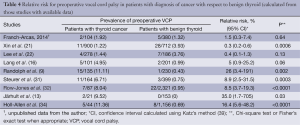

Relative risk for preoperative vocal cord palsy in patients with diagnosis of cancer with respect to benign thyroid is shown in Table 4. In most of the studies, a diagnosis of cancer increased the risk of VCP. This finding likely derived from the inclusion of patients with local advancer cancer, although this was not clearly stated in the eight studies. Everything considered, all patients with suspected invasive cancer—and perhaps also all patients with suspected or diagnosed cancer—should undergo preoperative laryngoscopy.

Full table

Previous surgery and the increased risk of vocal cord paralysis

Surgical injury is the most frequent etiology of VCP. While thyroid surgery remains the single most frequent operation associated with VCP, surgical procedures involving an anterior approach to the cervical spine, carotid endarterectomy, cardiothoracic surgery, and skull base surgery, are examples of non-thyroid procedures that also have been associated with postoperative VCP. Advances in thyroid surgery and the increasing implementation of these other procedures have increased the relative incidence of the latter as the major cause of VCP with a surgical etiology. Events associated with endotracheal intubation are also worth considering.

The association of revision (secondary) surgery with preoperative VCP could be evaluated based on data obtained from six of the reviewed studies, most of which showed a strong relationship between previous neck surgery and preoperative VCP. The relative risk for preoperative vocal cord palsy in patients with previous neck surgery is shown in Table 5; the data demonstrate that all patients with previous surgery, including the above-mentioned non-thyroid surgical procedures, should be scheduled for preoperative laryngoscopy.

Full table

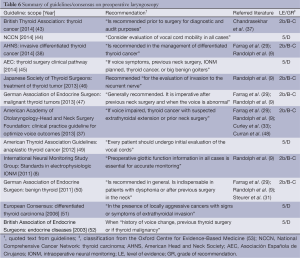

Recommendations on preoperative laryngoscopy from current guidelines

Several current guidelines regarding thyroid procedures, including those of the American Thyroid Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, European Thyroid Association, Spanish Association of Endocrinology and Nutrition, and The European Society for Medical Oncology, make no reference at all to laryngoscopy as part of the preoperative workup for thyroid nodules (12,40-42).

The positive recommendations provided by other guidelines are summarized in Table 6. Most of them agree regarding a routine policy for patients with thyroid cancer (37,38,43-47,49,52). The recent guidelines for anaplastic cancer from the American Thyroid Association also point out that preoperative laryngoscopy can be used to assess the opposite vocal cord, vocal cord mobility, endolaryngeal pathology, and potential disease extension into the subglottic or upper tracheal area (49). The European Consensus of 2006 recommends preoperative laryngoscopy only in patients with locally advanced cancer or symptoms (51). Two of the guidelines put forward a more general “recommended for all cases” policy statement, including cases of benign thyroid disease (8,50). The guideline on benign thyroid disease of the German Association of Endocrine Surgeons is somewhat ambiguous in that preoperative laryngoscopy “is recommended in general” but “is indispensable in patients with dysphonia or after previous surgery in the neck” (50).

Full table

The level of evidence of the recommendations from the examined guidelines (53) is low. Half of the recommendations are based on level 5 evidence (grade of recommendation D) and the rest on level 2b evidence (grade of recommendation B-C), and almost all of them referred to only two studies, those of Randolph et al. (9) and Farrag et al. (29).

The more specific “Clinical Practice Guideline for Optimize Voice Outcome,” from the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, recommends a selective policy when “voice impaired, thyroid cancer with suspected extrathyroidal extension or prior neck surgery” is present (37). It also notes that while preoperative laryngoscopy would be ideal in all patients undergoing thyroidectomy, the combined level of evidence is not high enough to expand the recommendation to all patients, including those with a normal voice and no prior neck surgery.

Is there a case for selective preoperative laryngoscopy?

Whether cases of VCP would remain undiagnosed if laryngoscopy was performed only in patients at high risk is unclear. With the adoption of a selective preoperative laryngoscopy approach, the risk of an undiagnosed VCP will never be equal to zero. Therefore, the important question is whether the magnitude of this risk may be considered as low as can be reasonably ascertained. Unfortunately, the data included in this review do not provide a definitive answer to the dilemma. Indeed, only 8 out of the 20 studies contain information that is useful in this regard, as they provide combined data on the number of preoperative VCPs in patients without voice symptoms, thyroid cancer, or previous neck surgery (9,14-16,22,25,29,31).

Three of these eight studies recommend routine laryngoscopy:

- Shin et al. recommended routine laryngoscopy “because glottic function cannot be predicted by voice assessment” (25). However, in their analysis of 198 patients, including 7 with preoperative VCPs, none were asymptomatic. Thus, if a selective laryngoscopy approach had been adopted, not a single case of VCP would have been missed.

- In the study by Farrag et al., among 292 patients, there were 5 with asymptomatic VCP associated with slowly progressive benign disease (29). However, whether these five patients were the same five who underwent revision surgery, also mentioned in the study, could not be determined from the data.

- Randolph et al. also strongly recommended routine laryngoscopy (9). However, according to their data, excluding carcinoma, there was only 1 patient with VCP among the 344 patients evaluated and he or she seems to have been symptomatic (data were unclear in this regard). In this series a selective preoperative laryngoscopy approach would not have resulted in undiagnosed cases of preoperative VCP.

The remaining five studies concluded that a selective approach may also be appropriate:

- In the study by Lang et al. the prevalence of asymptomatic VCP in a previously non-operated group of patients was 1/245 (0.41%) (16);

- In the study by Lee et al. only 1 out of 389 asymptomatic and previously non-operated patients had a VCP (0.25%) (22);

- In the study by Schlosser et al., among the 420 patients with neither voice symptoms, nor revision surgery, nor thyroid cancer, only 1 patient had preoperative VCP (0.23%) (15);

- In the 372 previously non-operated patients with benign thyroid disease evaluated by Steurer et al., there were 3 cases of preoperative VCP (0.8%) (31). Unfortunately it was unclear whether the three patients were asymptomatic;

- Finally, in the study by Yeung et al., the prevalence of VCP in asymptomatic patients was 1/142 (0.7%) (14).

A clear recommendation cannot be made based on the examined evidence. Whether a <0.5% risk of undiagnosed VCP is acceptable is a matter of debate.

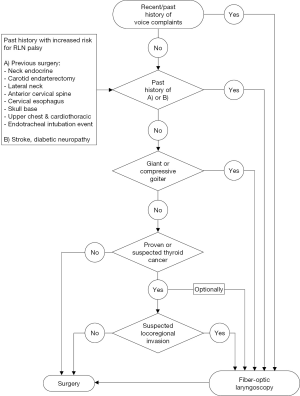

If a policy of selective preoperative laryngoscopy is adopted, then voice symptoms should be assessed through a careful history. However, in the following clinical settings, direct fiber-optic laryngoscopy should certainly be performed (Figure 1):

- Past or present history of hoarseness or change in voice quality, as noted by either the patient or the surgeon;

- History of prior surgery in which the RLN or vagus nerves may have been at risk for injury: thyroid/parathyroid operations, anterior cervical spine, carotid endarterectomy, cervical esophagus, lateral neck, skull base, cardiothoracic procedures and history of any adverse event associated with endotracheal intubation;

- Past history of stroke or diabetic neuropathy;

- Large retrosternal or compressive goiters;

- Suspicion of a locally advanced cancer or posteriorly situated malignancies. Optionally, all patients with thyroid cancer may be considered eligible for laryngoscopy.

Final remarks

Knowledge of the precise status of the vocal cords in all patients undergoing thyroid-related surgery is good practice for thyroid surgeons. The detection of a VCP preoperatively may modify the planned surgical technique, suggest invasive malignancy, or influence the management of an invaded nerve found at surgery. In addition, preoperative data provide an accurate baseline for postoperative laryngeal assessment. Only routine preoperative laryngoscopy may detect all VCPs. If preoperative laryngoscopy is performed only in patients at high risk (selective approach), a few VCPs (up to 0.5% of cases) will remain undetected. Whether the number of possible undetected palsies is as low as can be reasonably ascertained is a matter of debate.

Neither the necessary laryngoscopy equipment nor the skills required to perform the procedure may be universally available in endocrine surgery units. If the selective approach is adopted, then direct laryngoscopy is advised for all patients with present or past voice symptoms, a history of surgery in which the vagus and RLNs may have been at risk or any adverse events associated with endotracheal intubation, a past history of stroke or diabetic neuropathy, large retrosternal or compressive goiters, and in patients with a diagnosis or suspicion of advanced thyroid cancer.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dralle H. Thyroid incidentaloma. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of healthy persons with thyroid illness? Chirurg 2007;78:677-86. [PubMed]

- Chen AY, Jemal A, Ward EM. Increasing incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer in the United States, 1988-2005. Cancer 2009;115:3801-7. [PubMed]

- Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973-2002. JAMA 2006;295:2164-7. [PubMed]

- Hodin R, Clark O, Doherty G, et al. Voice issues and laryngoscopy in thyroid surgery patients. Surgery 2013;154:46-7. [PubMed]

- Randolph GW. The importance of pre- and postoperative laryngeal examination for thyroid surgery. Thyroid 2010;20:453-8. [PubMed]

- Sancho JJ, Pascual-Damieta M, Pereira JA, et al. Risk factors for transient vocal cord palsy after thyroidectomy. Br J Surg 2008;95:961-7. [PubMed]

- Bergenfelz A, Jansson S, Kristoffersson A, et al. Complications to thyroid surgery: results as reported in a database from a multicenter audit comprising 3,660 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008;393:667-73. [PubMed]

- Randolph GW, Dralle H; International Intraoperative Monitoring Study Group, Abdullah H, et al. Electrophysiologic recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring during thyroid and parathyroid surgery: international standards guideline statement. Laryngoscope 2011;121 Suppl 1:S1-16. [PubMed]

- Randolph GW, Kamani D. The importance of preoperative laryngoscopy in patients undergoing thyroidectomy: voice, vocal cord function, and the preoperative detection of invasive thyroid malignancy. Surgery 2006;139:357-62. [PubMed]

- American Association of Endocrine Surgeons (AAES). Fellowhip Programs. 2014. Available online: http://www.endocrinesurgery.org/fellowships/curriculum.html. Accessed November 22th 2014.

- Cobin RH, Gharib H, Bergman DA, et al. AACE/AAES medical/surgical guidelines for clinical practice: management of thyroid carcinoma. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. American College of Endocrinology. Endocr Pract 2001;7:202-20. [PubMed]

- Gharib H, Papini E, Paschke R, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, and EuropeanThyroid Association Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules. Endocr Pract 2010;16 Suppl 1:1-43. [PubMed]

- Järhult J, Lindestad PA, Nordenström J, et al. Routine examination of the vocal cords before and after thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Br J Surg 1991;78:1116-7. [PubMed]

- Yeung P, Erskine C, Mathews P, et al. Voice changes and thyroid surgery: is pre-operative indirect laryngoscopy necessary? Aust N Z J Surg 1999;69:632-4. [PubMed]

- Schlosser K, Zeuner M, Wagner M, et al. Laryngoscopy in thyroid surgery--essential standard or unnecessary routine? Surgery 2007;142:858-64; discussion 864. [PubMed]

- Lang BH, Chu KK, Tsang RK, et al. Evaluating the incidence, clinical significance and predictors for vocal cord palsy and incidental laryngopharyngeal conditions before elective thyroidectomy: is there a case for routine laryngoscopic examination? World J Surg 2014;38:385-91. [PubMed]

- Myssiorek D. Recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis: anatomy and etiology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2004;37:25-44. [PubMed]

- Rosenthal LH, Benninger MS, Deeb RH. Vocal fold immobility: a longitudinal analysis of etiology over 20 years. Laryngoscope 2007;117:1864-70. [PubMed]

- Schlosser K, Maschuw K, Hassan I, et al. Are diabetic patients at a greater risk to develop a vocal fold palsy during thyroid surgery than nondiabetic patients? Surgery 2008;143:352-8. [PubMed]

- Lorenz K, Abuazab M, Sekulla C, et al. Results of intraoperative neuromonitoring in thyroid surgery and preoperative vocal cord paralysis. World J Surg 2014;38:582-91. [PubMed]

- Xin J, Liu X, Sun H, et al. A laryngoscopy-based classification system for perioperative abnormal vocal cord movement in thyroid surgery. J Int Med Res 2014;42:1029-37. [PubMed]

- Lee CY, Long KL, Eldridge RJ, et al. Preoperative laryngoscopy in thyroid surgery: Do patients’ subjective voice complaints matter? Surgery 2014;156:1477-82; discussion 1482-3. [PubMed]

- Wong KP, Lang BH, Ng SH, et al. A prospective, assessor-blind evaluation of surgeon-performed transcutaneous laryngeal ultrasonography in vocal cord examination before and after thyroidectomy. Surgery 2013;154:1158-64; discussion 1164-5. [PubMed]

- Nam IC, Bae JS, Shim MR, et al. The importance of preoperative laryngeal examination before thyroidectomy and the usefulness of a voice questionnaire in screening. World J Surg 2012;36:303-9. [PubMed]

- Shin JJ, Grillo HC, Mathisen D, et al. The surgical management of goiter: Part I. Preoperative evaluation. Laryngoscope 2011;121:60-7. [PubMed]

- Wang CC, Wang CP, Tsai TL, et al. The basis of preoperative vocal fold paralysis in a series of patients undergoing thyroid surgery: the preponderance of benign thyroid disease. Thyroid 2011;21:867-72. [PubMed]

- Goretzki PE, Schwarz K, Brinkmann J, et al. The impact of intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM) on surgical strategy in bilateral thyroid diseases: is it worth the effort? World J Surg 2010;34:1274-84. [PubMed]

- Roh JL, Yoon YH, Park CI. Recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis in patients with papillary thyroid carcinomas: evaluation and management of resulting vocal dysfunction. Am J Surg 2009;197:459-65. [PubMed]

- Farrag TY, Samlan RA, Lin FR, et al. The utility of evaluating true vocal fold motion before thyroid surgery. Laryngoscope 2006;116:235-8. [PubMed]

- Chan WF, Lo CY, Lam KY, et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy in well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma: clinicopathologic features and outcome study. World J Surg 2004;28:1093-8. [PubMed]

- Steurer M, Passler C, Denk DM, et al. Advantages of recurrent laryngeal nerve identification in thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy and the importance of preoperative and postoperative laryngoscopic examination in more than 1000 nerves at risk. Laryngoscope 2002;112:124-33. [PubMed]

- Rowe-Jones JM, Rosswick RP, Leighton SE. Benign thyroid disease and vocal cord palsy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1993;75:241-4. [PubMed]

- Curley JW, Timms MS. Incidence of abnormality in routine 'vocal cord checks'. J Laryngol Otol 1989;103:1057-8. [PubMed]

- Holl-Allen RT. Laryngeal nerve paralysis and benign thyroid disease. Arch Otolaryngol 1967;85:335-7. [PubMed]

- Newcombe RG, Altman DG. Proportions and their differences. In: Altman DG, Machin D, Bryant TN, et al. eds. Statistics with confidence. London: British Medical Journal; 2000:45-56.

- Sittel C, Stennert E, Thumfart WF, et al. Prognostic value of laryngeal electromyography in vocal fold paralysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001;127:155-60. [PubMed]

- Chandrasekhar SS, Randolph GW, Seidman MD, et al. Clinical practice guideline: improving voice outcomes after thyroid surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;148:S1-37. [PubMed]

- Shindo ML, Caruana SM, Kandil E, et al. Management of invasive well-differentiated thyroid cancer: an American Head and Neck Society consensus statement. AHNS consensus statement. Head Neck 2014;36:1379-90. [PubMed]

- Morris JA, Gardner MJ. Epidemiological studies. In: Altman DG, Machin D, Bryant TN, et al. eds. Statistics with confidence. London: British Medical Journal; 2000;57-72.

- American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer, Cooper DS, Doherty GM, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2009;19:1167-214. [PubMed]

- Gómez Sáez JM. Taking of position in relationship to the protocol of the current treatment of thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocrinol Nutr 2010;57:370-5. [PubMed]

- Pacini F, Castagna MG, Brilli L, et al. Thyroid cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2012;23 Suppl 7:vii110-9. [PubMed]

- Perros P, Boelaert K, Colley S, et al. Guidelines for the management of thyroid cancer. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;81 Suppl 1:1-122. [PubMed]

- NCCN. Thyroid Carcinoma. In: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2014. Available online: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thyroid.pdf. Accessed November 22th 2014.

- Colina-Alonso A, Flores-Pastor B, Gutiérrez-Rodríguez MT, et al. eds. Clinical Pathway for Thyroid Surgery. 2014 ed. Madrid: Asociación Española de Cirujanos; 2014.

- Takami H, Ito Y, Noguchi H, et al. eds. Treatment of thyroid tumor. Japanese clinical guidelines. 2013 ed. Tokyo: Springer Japan; 2013.

- Dralle H, Musholt TJ, Schabram J, et al. German Association of Endocrine Surgeons practice guideline for the surgical management of malignant thyroid tumors. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2013;398:347-75. [PubMed]

- Curran AJ, Smyth D, Sheehan SJ, et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve dysfunction following carotid endarterectomy. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1997;42:168-70. [PubMed]

- Smallridge RC, Ain KB, Asa SL, et al. American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2012;22:1104-39. [PubMed]

- Musholt TJ, Clerici T, Dralle H, et al. German Association of Endocrine Surgeons practice guidelines for the surgical treatment of benign thyroid disease. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2011;396:639-49. [PubMed]

- Pacini F, Schlumberger M, Dralle H, et al. European consensus for the management of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma of the follicular epithelium. Eur J Endocrinol 2006;154:787-803. [PubMed]

- British Association of Endocrine Surgeons (BAES) Guidelines and Training Sub-Group. Guidelines for the surgical management of endocrine disease and training requirements for endocrine surgery. 2003. Available online: http://www.baets.org.uk/guidelines. Accessed November 22th 2014.

- OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2011. Available online: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653. Accessed December 19th 2014.